In [Part 1], I built a pipeline to churn through gigabytes of drivers. I started with a massive raw dataset of 58.5 GB of drivers. However, feeding this volume into a static analyzer is inefficient. I aggressively filtered the set:

- Deduplication: Removing duplicate hashes cut the numbers significantly.

- Size Limits: I excluded files larger than 100MB, which are typically installers or bundles rather than pure drivers.

This left me with a curated dataset of 28,000 unique drivers and a lot of optimism. I frankly expected to find something significant, maybe a novel class of bugs in a major EDR driver, or a complex logical flaw that no one had seen before.

I narrowed the 28,000 down to 467 high-risk drivers. But to be honest? The findings were… lackluster.

Initial Findings & Hypothesis Refinement

When observing drivers at this scale using static analysis tools like IOCTLance, certain patterns quickly emerge. IOCTLance is effective at flagging well-understood vulnerability classes such as missing Access Control Lists (ACLs), raw pointer dereferences, or unconstrained buffer copies.

These “textbook” bugs, while critical, are surprisingly common.

I didn’t find sophisticated backdoors or complex race conditions. Instead, I found a pattern of recurring simple oversights:

- Trivial IOCTLs: Drivers that literally expose

ReadPortandWritePortto “Everyone”. It’s like leaving your front door open, but for kernel memory. - Ancient Code: Drivers signed in 2023 that were clearly compiled from source code written in 2009. The digital signature says “Modern”, but the assembly says “Windows 7”.

- False Positives: Tools often flag potential issues in code paths that may be practically unreachable without high privileges (e.g., SYSTEM).

I realized that discovering the vulnerability is only the first step. The more complex challenge is understanding why these issues persist. These patterns are pervasive enough to suggest they are systemic traits of the driver supply chain rather than isolated errors.

Shifting Focus: Enter AutoPiff

If vulnerability discovery is relatively well-understood, the more compelling question becomes: How does this ecosystem evolve?

When a vendor like Fortinet or Cisco quietly patches a vulnerability in their base driver, what happens to the 50 other OEMs re-branding that same driver? Do they patch it? Or does the ecosystem fragment into a mess of “secure” and “vulnerable” versions of the exact same code?

This thought process led me to build AutoPiff (Automated Patch Diffing).

How It Works: Semantic Diffing

AutoPiff isn’t just a diff tool. It doesn’t care if line 400 changed. It cares about SEMANTICS. It uses a rule engine based on Sinks and Guards.

- The Sink: A dangerous operation (e.g.,

memmove,MmMapIoSpace). - The Guard: A safety check (e.g.,

if (size < buffer_len)).

If AutoPiff sees a memmove in Version 1 that gains a Guard in Version 2, it flags a “Silent Patch”, indicating a security improvement was made without a corresponding advisory.

Exploring the Families

Using AutoPiff and targeted batch downloads, I started digging into specific driver families to see the “Copy-Paste” epidemic in action.

1. DDK Sample Usage (wnPort32.sys)

I identified 10 signed drivers that are literally compiled versions of the Windows (R) Win 7 DDK driver sample.

- Analysis: These appear to be educational samples provided by Microsoft. It seems some developers may compile and sign them for convenience, potentially overlooking the need to remove testing interfaces before distribution.

- The Reality: These drivers are often intended for learning, not production. Their continued use suggests a reliance on legacy code for simple hardware access.

Verification: The Open Door

The driver initializes a device object with zero characteristics and no security descriptor, making it accessible to any user. The dispatch routine processes READ_PORT/WRITE_PORT IOCTLs without privilege checks.

// Decompiled wnPort32.sys Dispatch Routinecase 0x80102050: // IOCTL_WINIO_READPORT DbgPrint("IOCTL_WINIO_READPORT"); if (InputBufferLength != 0) { memcpy(&local_40, UserBuffer, InputBufferLength); // Copy port number if (Size == 1) { // Direct Hardware Access via READ_PORT_UCHAR Result = READ_PORT_UCHAR(local_40); } // ... Copy result back to user } break;2. SDK & White Label Issues

I found a specific Null Pointer Dereference pattern in 140 different drivers.

- The Culprits: Fingerprint Sensors (

egis_technology) and Smart Card Readers. - The Implication: This suggests a shared vulnerability source, likely an SDK used by multiple vendors. Addressing this would require fixing the upstream component.

Verification: The Unsafe Deference

In FPSensor.sys, verified to be the Egis “White Label” driver found in 140+ products, we found a critical METHOD_NEITHER IOCTL (0x223c07). The driver directly dereferences a user-supplied pointer (Type3InputBuffer) without any ProbeForRead or try/except block, leading to an immediate crash (Null Pointer Dereference) or Arbitrary Read if an invalid address is passed.

// Decompiled FPSensor.sys (IOCTL 0x223c07 - METHOD_NEITHER)if (uVar3 == 0x223c07) { // Type3InputBuffer is a USER MODE pointer in METHOD_NEITHER // DANGER: Dereferencing User Pointer without ProbeForRead! lVar17 = **(longlong **)(IrpStack + 0x20); // If User passes 0, this crashes immediately (Null Dereference) // If User passes kernel address, it attempts to read it uVar6 = ObReferenceObjectByHandle(lVar17, ...);}This confirms the “Null Pointer Dereference” signature is effectively an unsafe handling of User Mode Pointers in a METHOD_NEITHER IOCTL.

3. VPN Driver Analysis (Cisco & Fortinet)

To make sense of the massive code reuse in VPN drivers, I built a custom dashboard to plot the Match Rate of a driver’s code against its previous version.

The dashboard itself is backed by a custom Karton microservice that listens for new driver uploads. When a new version of a tracked driver appears, the service automatically fetches the previous version, runs the diffing engine, calculates the match rate, and pushes the result to the dashboard in real-time.

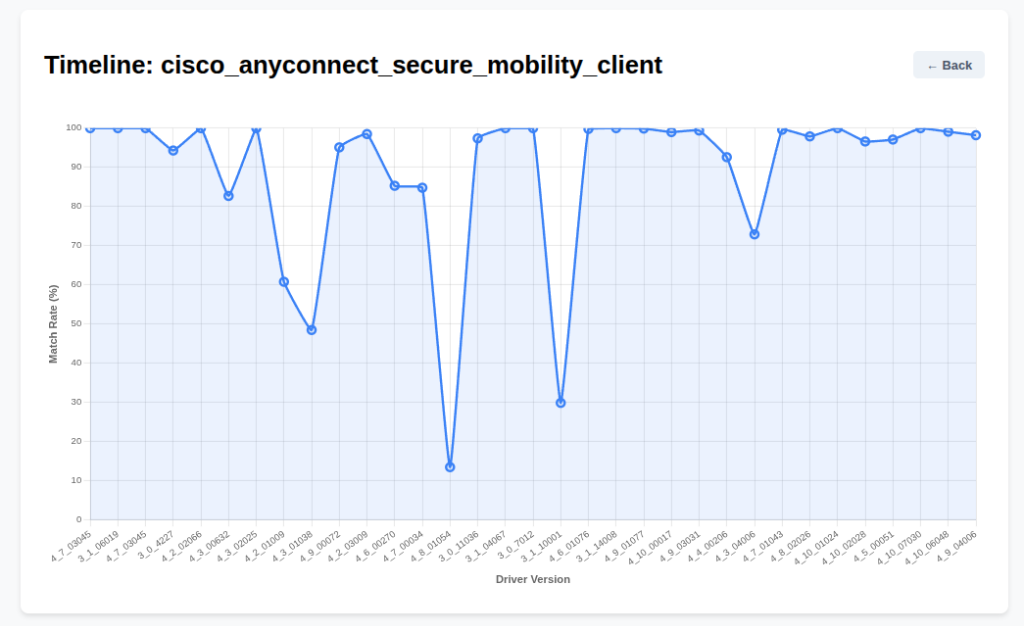

Case Study A: Cisco AnyConnect (acsock64.sys)

The timeline for Cisco is remarkably stable. You see a consistent high match rate, indicating disciplined code maintenance. However, specific versions show match rate dips that correlate to security hardening updates, likely responding to IPC vulnerabilities like CVE-2020-3433 or privilege escalation flaws like CVE-2023-20178. The visual ‘dip’ is the footprint of a security team fixing a bug.

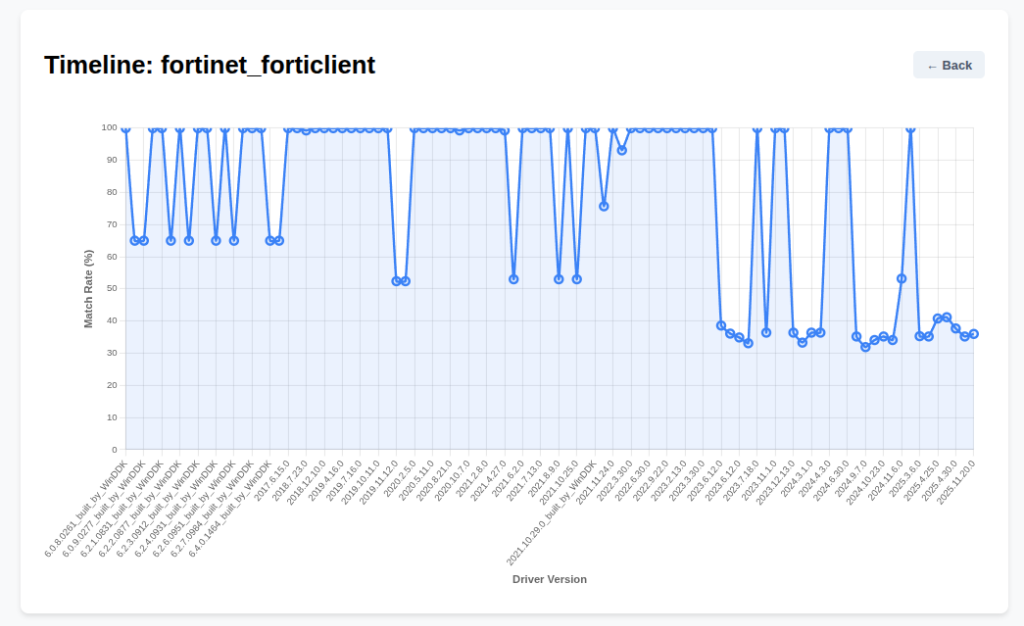

Case Study B: Fortinet FortiClient (fortips*.sys)

The Fortinet timeline features ‘100% Match’ plateaus, confirming that the driver binary often didn’t change at all between versions.

However, fortips.sys is a known hotspot. Recent disclosures like CVE-2025-47761 (Exposed IOCTL) and CVE-2025-46373 (Buffer Overflow) confirm that this driver has been vulnerable. The sharp drops in the timeline (e.g., in late 2025 versions) explicitly correlate with the massive refactoring required to patch these vulnerabilities.

From Bug Hunting to Ecosystem Analysis

While finding individual vulnerabilities like those in Cisco or Fortinet is valuable, it doesn’t solve the systemic problem. My initial goal was simply to catch bugs, but that evolved into something larger: understanding the whole ecosystem of developing drivers, what gets changed, how often patches are applied, and how these changes propagate.

By combining mass-downloading (via VT) with semantic diffing (AutoPiff), I’m moving away from just pointing at a buggy driver. I’m building an observatory that can answer:

- Who is patching silently?

- Who is still using a 10-year-old vulnerable SDK?

- Can we automate the “Proof”?

Currently, verifying a driver requires manual effort: two VMs (Target + Debugger), attaching WinDbg, copying the driver + POC, creating a service, and executing it to catch the crash.

I am currently experimenting with MCP (Model Context Protocol) to orchestrate this. The goal is to have an LLM interact with both VMs, run the POC, and interpret the bugcheck code. While challenging due to tool limitations (e.g., vmrun), I am making steady progress. (More on this in Part 3)

Community Feedback & Future Directions

I received some great feedback on Part 1, and it’s shaping where this project goes next:

- Continuous Monitoring / LOLDrivers: Thanks to Michael H. and the LOLDrivers team for the support! The goal is to feed high-quality data back into the community.

- VT Ingestion: I took eversinc33‘s suggestion to “ingest every newly submitted .sys file” and adapted it. Instead of drinking from the firehose, I used VirusTotal to selectively study the kernel drivers of specific high-value products (like VPNs) to track their patch history.

- Cert Graveyard: Gootloader suggested checking signatures against @SquiblydooBlog‘s Cert Graveyard. However, as Squiblydoo clarified, their focus is on code-signing abuse rather than vulnerable drivers, so I likely won’t be integrating this particular feed.

A Personal Note

On a lighter note, building this automated system has been incredibly fun. Now, whenever I find an interesting driver, I can just download it and upload it to my MWDB instance. The system handles all the heavy lifting (analysis, diffing, and tagging) automatically. It transforms research from a chore into a simple query.

In Part 3, I will focus on two key challenges: further accelerating static analysis to handle the sheer volume of drivers, and scaling up the automated generation and testing of Proof-of-Concept exploits.

Leave a comment